Andry3

Andry Street Updates & Things

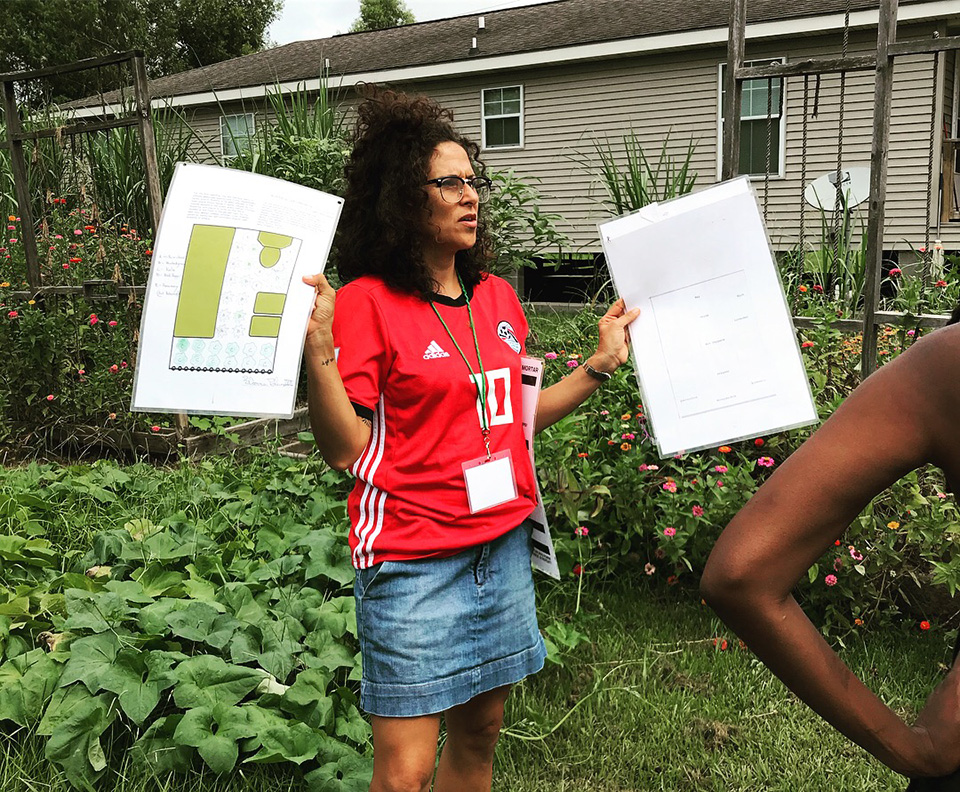

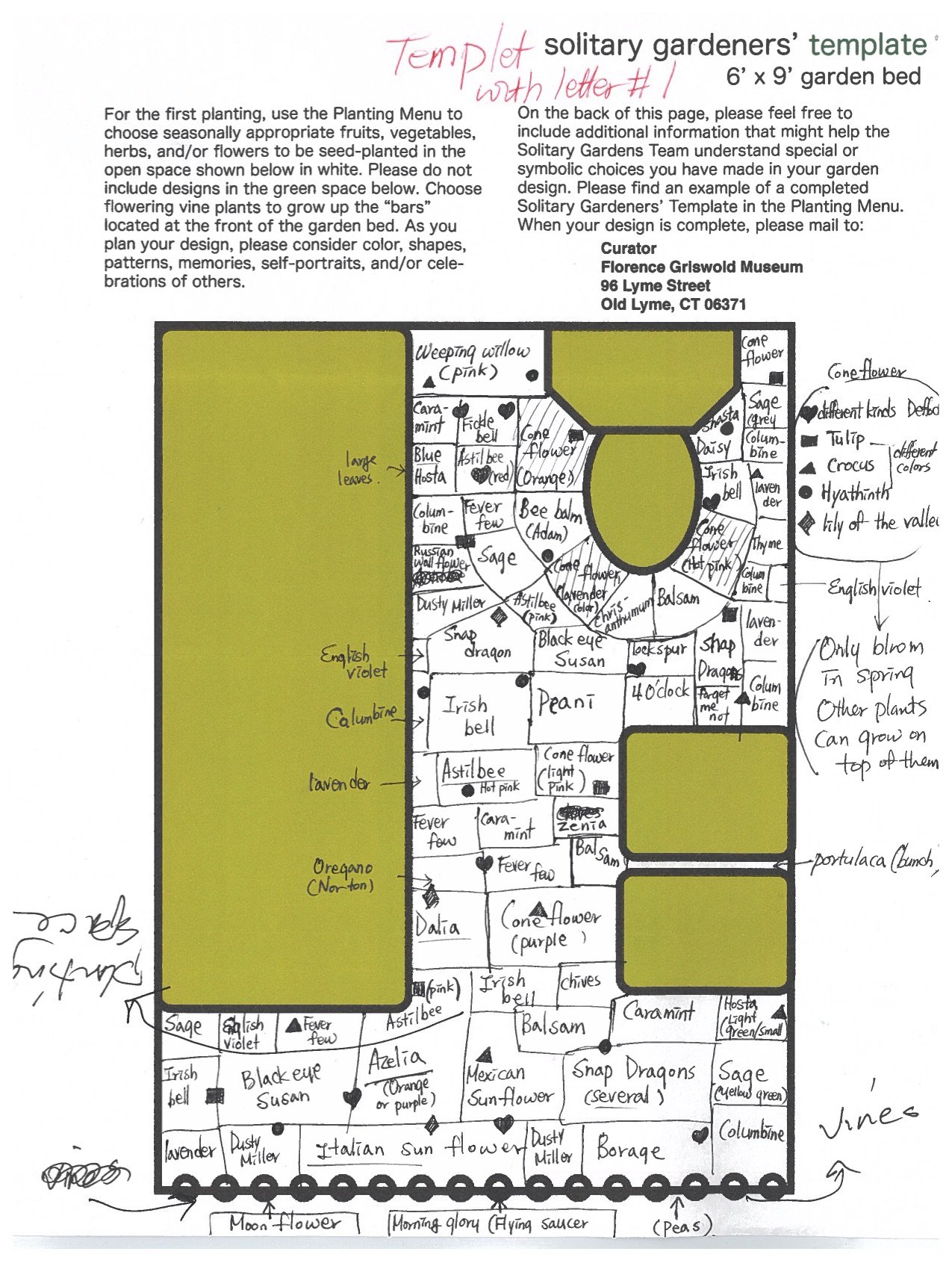

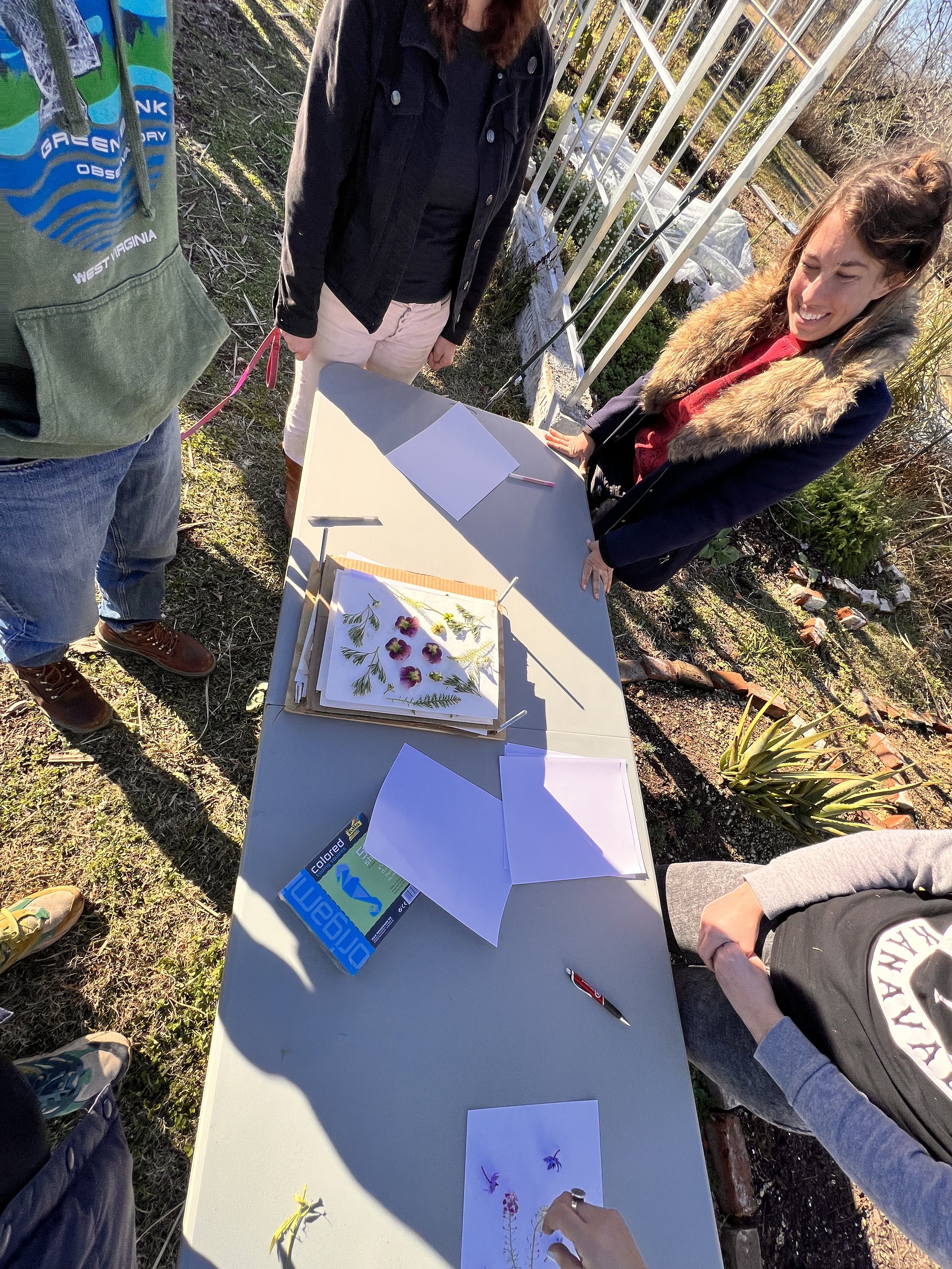

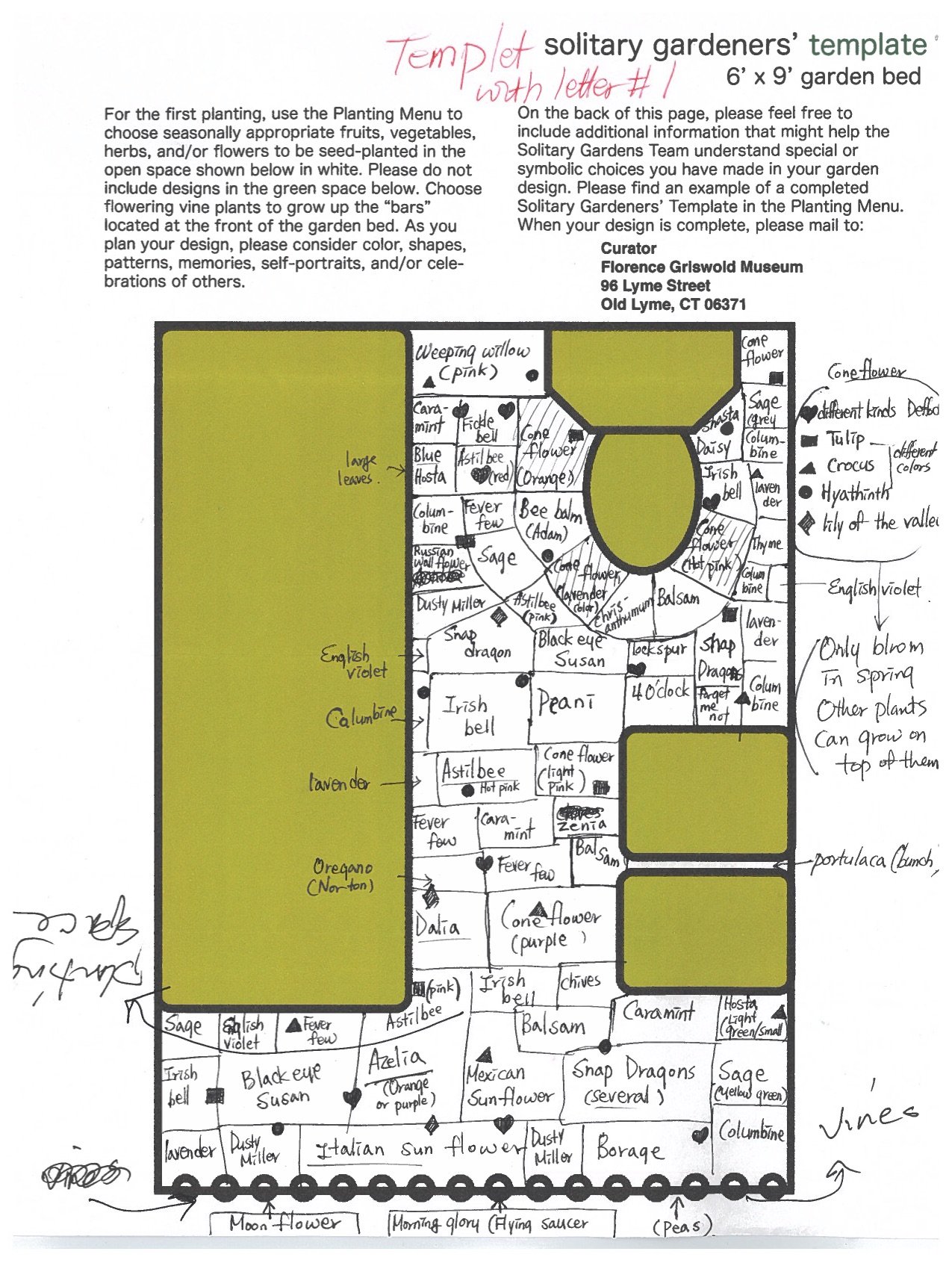

Growing takes time. Unlearning systems of oppression, like growing a plant, requires daily attention and care. Love, hope, compassion, and social equity require nurturing in order to fully blossom. In year three, we hit our stride. After many attempts we figured out the recipe for Revolutionary Mortar, we built several new garden beds on site, we met more Solitary Gardeners , went on tour, twice & started a whole new abolitionist initiative called Growing Abolition, and published a new book The Abolitionist’s Fieldguide. It has been exhausting, impossible and beautiful all at the same time. Currently we have dozens of Solitary Gardens around the country. We began with nine beds in New Orleans at our Andry Street location. We spend a lot of time in the garden and as a result, update more often at our IG feed @SolitaryGardens— please check us out there for relevant information and volunteer times!

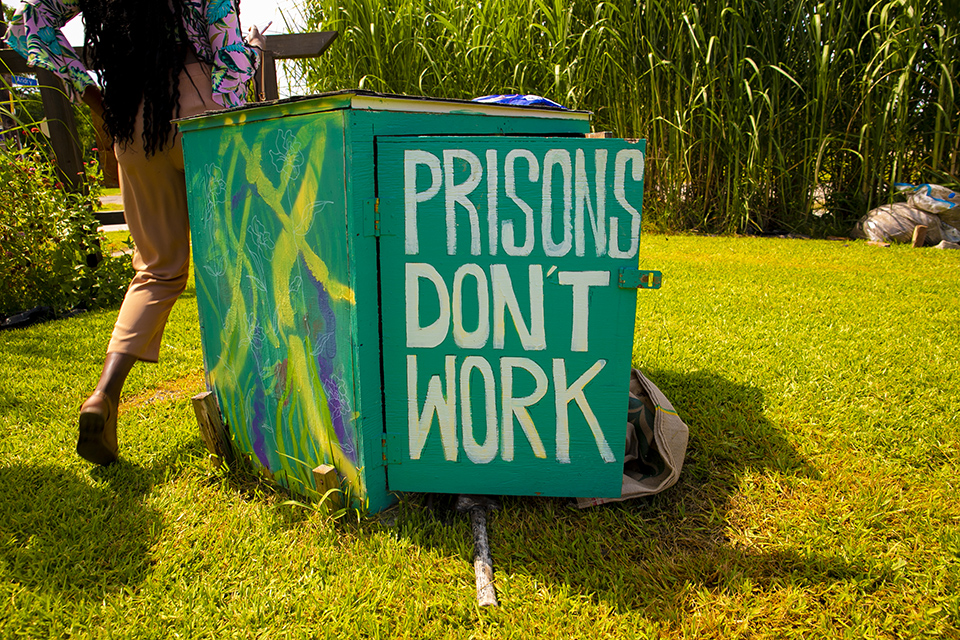

Prison Abolition

Prison abolition is at the heart of this project. The Andry Street Site, allowed us to create the visual of a prison tier (9-Solitary Gardens in a row) that will naturally disappear overtime. Working with the theories of implicit bias, we hope folks will witness these prisons cells vanish and somewhere in their subconscious believe it is possible to exist in a landscape without prisons. It sure can! To learn more about this work and how it continues to grow check out Growing Abolition.

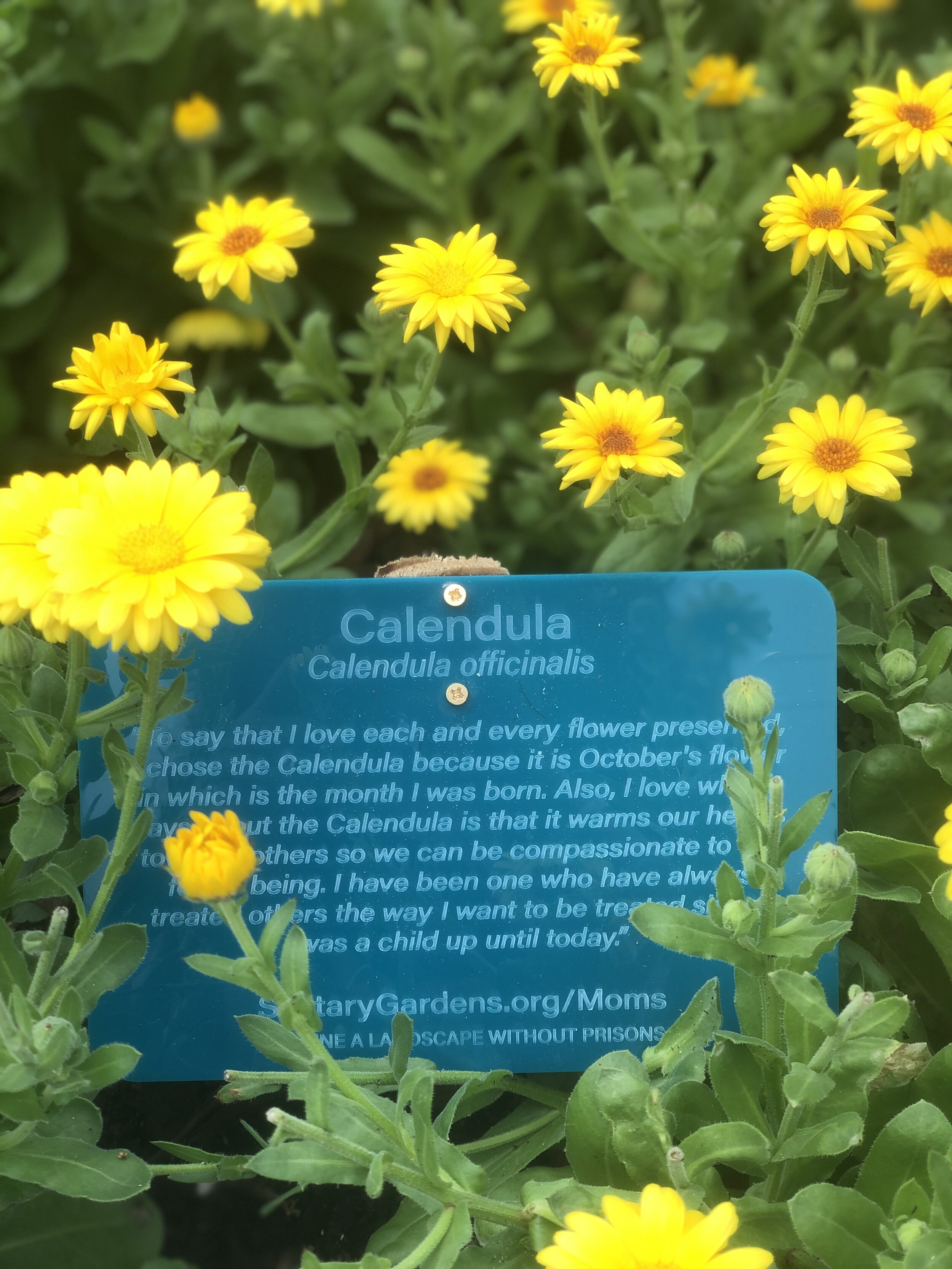

Growing Compassion

Through the act of (metaphoric and literal) gardening, this project will demonstrate how ignoring the vitality of other beings impoverishes our own imaginations and collective well being.The Solitary Gardens is a social sculpture and collaborative project that galvanizes compassion and cultivates conversations alternatives to incarceration. This project directly and metaphorically asks us to imagine a landscape without prisons.

So much work for love to do

Central to this project are the questions: How can we collectively stand at the intersection of creative and spiritual practices to address the wounds of the past? How do we recognize our complicity in systems of oppression as well as our power? How do we interrupt the dominant culture’s dependency on punishment, retribution to address so-called crimes in our community? In a society whose imagination is crippled by personal and collective trauma, it is important to illustrate not only what is wrong with this system of injustice, but also what is possible.